Hashcash

N.B: This post was originally written by Haseeb Qureshi and published on nakamoto.com on December 29, 2019.

Hashcash was an early precursor to digital cash. Satoshi cited it as his inspiration for the proof-of-work implementation in Bitcoin. To understand Bitcoin's consensus mechanism and proof-of-work, we first have to contend with Hashcash. Luckily, Hashcash is simple enough that we'll be implementing it ourselves by the end of this lesson.

Hashcash was invented by Adam Back in 1997 as a way to prevent email spam. Even in 1997, email spam was a nuisance to anyone with an email account. Adam Back realized this was because of a fundamental problem: all you needed to email someone was send a few packets to a mail server. Sending an email was so inexpensive as to be basically free. Honest users only ever sent a handful of emails a day, and yet spammers could send tens of millions at almost no cost.

So why not raise the price of entry?

Imagine sending an email cost a penny. To a normal user, this is fine—they have a few pennies to spare each day. But a spammer would have to pay up millions of pennies, making their spam campaigns impossible.

You might notice this is a bit circular: charging a penny per email implies the existence of digital pennies to pay with. But we established earlier that no such solution existed—that's why we needed Bitcoin! (And normal payment rails wouldn't suffice, since credit cards charge a lot more than a penny in fees for any transaction.)

So how could Hashcash force spammers to cough up a digital penny? The answer lies in the core idea behind Hashcash, which is now also integral to Bitcoin: proof-of-work.

Proof-of-work

The notion of proof-of-work (PoW) was first invented by two cryptographers, Cynthia Dwork and Moni Naor, though Adam Back also arrived at the idea independently when he created Hashcash.

A PoW is a computational proof that some work has been performed. Usually, this is implemented through a computational puzzle. The puzzle should be:

easy to state (find me a needle in this haystack)

hard to solve (the haystack is big)

easy to verify (yep, that's a needle)

Generating a solution to the puzzle serves as evidence that the solver performed some work. If we make this puzzle hard enough, we can be satisfied that it would cost about a penny of work (in hardware depreciation and electricity costs). We can then say: okay, you expended a penny of work, you can send me that email.

In their original paper, Dwork and Naor suggest several candidate PoW functions, such as taking square roots in a finite field. Other researchers proposed schemes such as generating arbitrary hash collisions. But Adam Back proposed a much simpler PoW algorithm, which would eventually be adopted by Satoshi in Bitcoin: generating a hash digest with a specified prefix.

Hashcash's proof-of-work

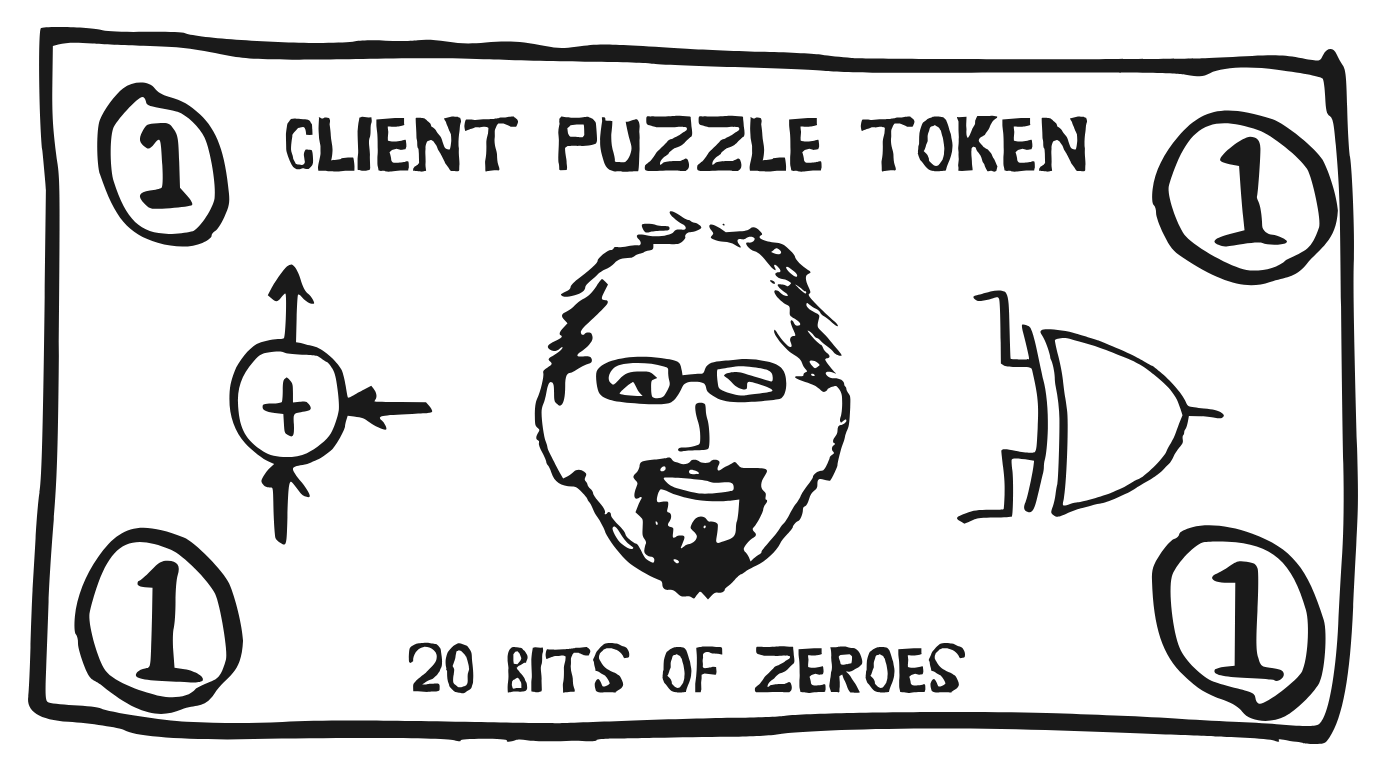

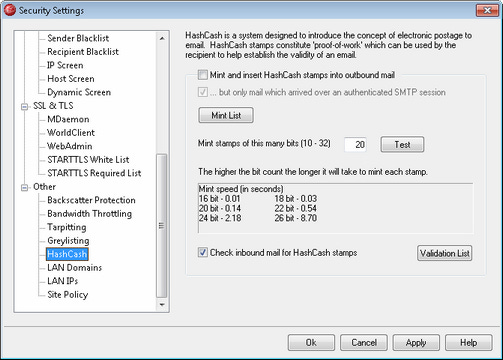

Hashcash's proof-of-work is pretty straightforward. First, the mail server specifies a difficulty level, a number that defines how hard the PoW must be. The default is 20. The proof of work in Hashcash is then to generate a message whose SHA-1 hash digest starts with 20 zeros in binary.

How can you create a hash digest with a specified prefix? Remember, with a cryptographic hash function, you shouldn't be able to predict the output any better than random. This means you have no choice but to brute force it. To solve this PoW, you just keep trying different inputs until one of them happens to have enough 0s in front of it.

The input you grind through is generally called the nonce. Let's try iterating through a few nonces and see if we can generate a single leading leading zero in hexadecimal (equivalent to a four 0s in binary). We'll make our nonce always start with "Here we go!"

from hashlib import sha1

sha1(b"Here we go!00").hexdigest()

# '2bf6d36bf9b140c2a62c66d79f6bd578dccdc141'

sha1(b"Here we go!01").hexdigest()

# 'cd7810e0446a26b4a4e7c1773989050d9fe798a2' => Nope

sha1(b"Here we go!02").hexdigest()

# '3fbf1f91e1a212c66f65786040bb25cc91f4598b' => Nope

sha1(b"Here we go!03").hexdigest()

# '2ad11aff9dd50f5e8641862638db2ff8420b89b8' => Nope

sha1(b"Here we go!04").hexdigest()

# '173ba0b3dc1adbce286c4ba9ea62199ab659e608' => Nope

sha1(b"Here we go!05").hexdigest()

# '076174d1a153e87da3248278132b007cf6adb701' => Ding ding ding!Okay, so how difficult is it to generate a hashcash PoW with a difficulty level of N

bits? Since each bit of your digest has an equal likelihood to be 0 or 1, it should take about 2^20 iterations to get 20 zeros in a row. Every additional 0 doubles the difficulty. Here's the intuition: each additional bit you require invalidates half of the previously valid digests.

If you think about it, this is amazing. I can show you some random bytes, and if you hash them and see 64 zeros, then you know that I spent about $100 hashing to find that value. Hashcash lets you represent real-world costliness in cyberspace via just a random-looking number. This idea has deeply important implications for Bitcoin, as we'll explore in later modules.

Mitigating double spends

Hashcash's PoW is simple and elegant, but we've still got the deal with the scourge of digital money: double spends.

A naive implementation of Hashcash suffers from a nasty double spend problem. What's to stop a spammer from just generating one really difficult hashcash token, and then using the same token for every email they send?

We need some way to prevent repeat spending of Hashcash tokens. Hashcash has two simple mechanisms for this.

The first is limiting each hashcash token to a specific email address, so they're not reusable for different recipients. This is done by forcing the hashed token to include a string specific to that email address.

The original Hashcash format is as follows: VERSION:DATE:EMAIL_ADDRESS:NONCE. First, the Hashcash protocol version (for future versioning), today's date, the recipient's email address, and then the nonce you randomly churn through until you find one that makes the whole thing satisfy the difficulty level. The token is then included as an X-Hashcash header in the SMTP request.

You can see some Hashcash tokens Adam Back generated on the Hashcash website, such as this one:

from hashlib import sha1

sha1(b"0:030626:adam@cypherspace.org:6470e06d773e05a8").hexdigest()

# '00000000c70db7389f241b8f441fcf068aead3f0'This hashcash digest has 8 leading zeros in hex, equivalent to 32 leading zeros in binary. This means it should've taken roughly 2^32 iterations to find this nonce.

Forcing the token to include the email and date solves the problem of using a single Hashcash token to spam multiple recipients. But there's still one problem here. I can reuse the same Hashcash token on the same person. What's to stop me from sending it 1,000 times to the same person in the same day?

To mitigate this, Hashcash requires the email server to remember any Hashcash tokens received in the last day. If it has already seen a certain token that day, then the solution is rejected. For most servers, this should only demand a small amount of memory. With these protections in place, it should no longer be possible to double spend Hashcash tokens.

Hashcash was a clever design, but it didn't take off on a large scale. After email services centralized into a few companies with massive data sets (Gmail, Yahoo, MSN, etc.), those companies were able to mitigate most email spam through machine learning and email reputation systems. Centralization ended up producing non-economic solutions to spam prevention, obviating the need for Hashcash.

But Hashcash was a very important stepping stone in getting the cypherpunks closer to the vision of digital cash. And its application of proof of work was a direct precursor to Bitcoin.

Assignment

For your next assignment, you'll be implementing a Hashcash server. The assignment has two parts: first, you'll be writing a Hashcash token validator, and then you'll be writing a Hashcash token minter that actually computes a PoW.

Save this code, as it'll definitely be useful for your cryptocurrency!

Once you've got all the tests passing, you're ready to move on.

Additional reading

Pricing via Processing or Combating Junk Mail by Cynthia Dwork and Moni Naor (1992)

Hashcash white paper by Adam Back (1997)

Hashcash developer guide by Adam Back (2004)

Hashcash Auctions for Decentralized Resource Allocation by Chris McCormick (2018)